Western Sahara: Africa’s Last Colony and the Struggle for Self-Determination

Introduction

In the sweeping deserts of North Africa, Western Sahara stands as one of the world’s most protracted territorial disputes—a conflict between Morocco and the Sahrawi people that has persisted for nearly half a century. Known for its rich phosphate deposits and valuable coastline along the Atlantic, Western Sahara’s significance goes beyond its natural resources. For the Sahrawi people, it represents a homeland and a dream of self-determination; for Morocco, it is a “southern province,” an integral part of the nation. This long-standing dispute has drawn in neighboring Algeria, major global players, and the United Nations, but despite decades of negotiations, resolutions, and a frozen ceasefire, peace remains elusive. Western Sahara is more than a forgotten conflict; it is a case study in colonial legacy, national identity, and the enduring power struggle over sovereignty and rights.

Colonial Legacy: Spain’s Role and the Road to Conflict (1884–1975)

The roots of the Western Sahara conflict can be traced back to European colonialism. In 1884, Spain claimed control over the region, establishing the colony known as Spanish Sahara. For nearly a century, Spanish authorities exploited the territory’s resources, particularly its phosphate mines, but left the Sahrawi population with little economic or political empowerment. Meanwhile, the people of Western Sahara maintained their own cultural identity, with deep tribal and linguistic ties to the region and a desire for autonomy.

In the early 1960s, as decolonization swept across Africa, the United Nations called for Spain to decolonize Western Sahara. In response, the Sahrawi independence movement began to take shape, with organizations like the Polisario Front (Frente Polisario) emerging to advocate for self-determination. Founded in 1973, the Polisario Front sought to end Spanish rule and establish an independent Sahrawi state. However, Spain delayed its exit, and by the mid-1970s, Western Sahara’s future had become a point of contention between Morocco and Mauritania, both of which laid claim to the region.

The Green March and Moroccan Control (1975–1976)

In 1975, as Spain prepared to withdraw, Morocco’s King Hassan II made a dramatic move to assert Moroccan claims over Western Sahara. In a calculated display of nationalism, Hassan organized the “Green March,” in which approximately 350,000 Moroccan civilians crossed into Western Sahara, claiming it as part of Morocco’s “historic lands.” This maneuver, combined with military force, was meant to signal Morocco’s commitment to the territory.

Under pressure, Spain agreed to divide control of Western Sahara between Morocco and Mauritania, ignoring the Sahrawi call for independence and bypassing the Polisario Front. The Madrid Accords of 1975 formalized this arrangement, but it left the Sahrawis disenfranchised and sparked a new phase in the conflict. The Polisario Front, with support from neighboring Algeria, rejected the partition and launched a guerrilla war against both Morocco and Mauritania, seeking full independence for Western Sahara.

Guerrilla Warfare and the Moroccan Wall (1976–1991)

The late 1970s and 1980s were marked by intense conflict between the Moroccan military and the Polisario Front. Mauritania, facing mounting casualties and economic strain, withdrew from Western Sahara in 1979, leaving Morocco to control the majority of the territory. Morocco then claimed full sovereignty over Western Sahara, solidifying its control over key cities and resources.

In response, the Polisario Front intensified its guerrilla tactics, operating out of refugee camps in Algeria and launching attacks on Moroccan forces. To counter this, Morocco constructed a fortified sand wall, or “berm,” stretching over 1,700 miles across Western Sahara. Heavily mined and guarded by tens of thousands of Moroccan soldiers, the wall effectively divided the territory, with Morocco controlling the western portion and the Polisario maintaining influence in the eastern areas and the refugee camps in Algeria. The wall, still standing today, has become a symbol of the unresolved division between the two sides.

The Ceasefire and UN Peacekeeping Mission (1991)

In 1991, after years of violent conflict, the United Nations brokered a ceasefire agreement between Morocco and the Polisario Front, establishing the United Nations Mission for the Referendum in Western Sahara (MINURSO). The mission’s primary goal was to organize a referendum allowing the people of Western Sahara to choose between independence and integration with Morocco.

However, disputes over voter eligibility and Morocco’s reluctance to proceed with the referendum led to repeated delays. MINURSO remains in place to this day, making it one of the UN’s longest-running peacekeeping missions. While the ceasefire halted open hostilities, the promised referendum has never taken place, and the territory remains divided between Moroccan-controlled areas and Polisario-administered zones. For the Sahrawi people, the promise of self-determination remains unfulfilled, and the region is effectively in a state of “frozen conflict.”

Morocco’s Autonomy Plan and Diplomatic Shifts (2000s–2020s)

In the early 2000s, Morocco proposed an autonomy plan as an alternative to full independence for Western Sahara. Under this plan, Western Sahara would be granted a degree of self-governance, while remaining under Moroccan sovereignty. Morocco has argued that the autonomy plan is a fair compromise, particularly given the kingdom’s investment in infrastructure and development projects in the region. However, the Polisario Front and its ally Algeria rejected this proposal, insisting on a referendum that includes the option for independence.

The diplomatic landscape around Western Sahara shifted dramatically in 2020, when the United States, under President Donald Trump, recognized Moroccan sovereignty over Western Sahara in exchange for Morocco’s normalization of relations with Israel. This marked a significant departure from the U.S.’s previous neutrality and further complicated the conflict. Several other African and Arab nations have since aligned with Morocco’s position, though the UN and much of the international community continue to view Western Sahara as a “non-self-governing territory” with a right to self-determination.

The Human Cost: Refugees and Life in the Camps

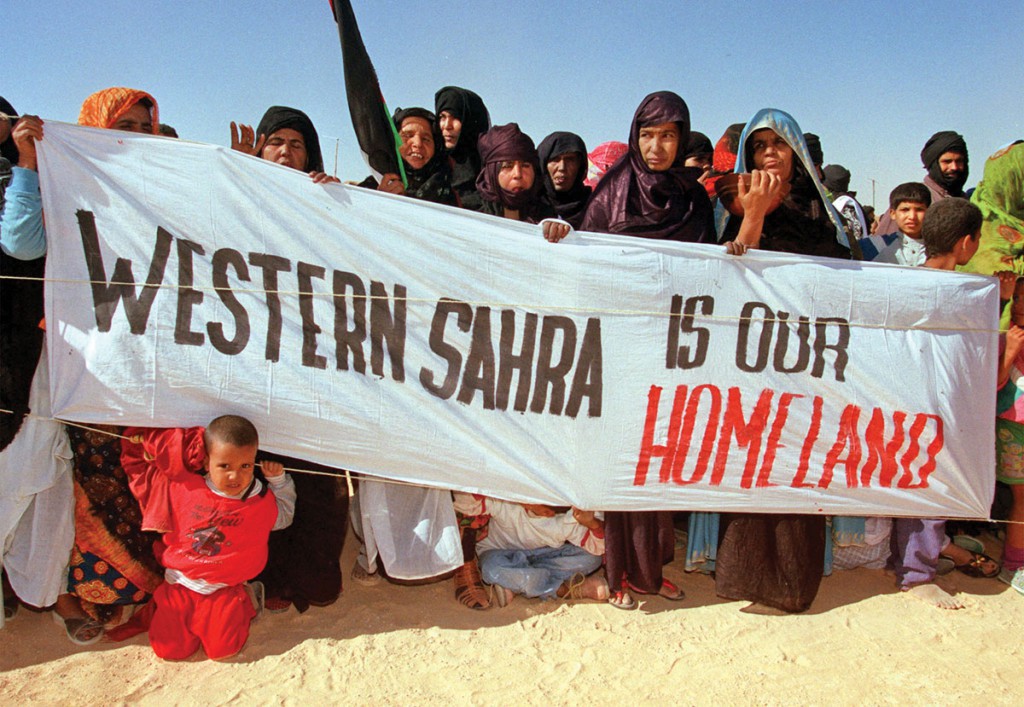

The ongoing conflict has exacted a heavy toll on the Sahrawi people, many of whom have lived in refugee camps in Algeria for generations. The camps, located near the Algerian town of Tindouf, are home to approximately 175,000 Sahrawis who fled the conflict in the 1970s and 1980s. Managed by the Polisario Front, the camps rely on international aid and face challenges related to food insecurity, harsh living conditions, and limited economic opportunities. For young Sahrawis born in the camps, life is marked by a sense of displacement, frustration, and a fading hope of returning to their homeland.

Within Moroccan-controlled Western Sahara, the Sahrawi population faces a different set of challenges. Human rights groups have reported restrictions on freedom of speech, surveillance, and harassment of pro-independence activists. Morocco has heavily invested in the region’s infrastructure and economy, attracting settlers and seeking to integrate Western Sahara more closely with the rest of the kingdom. However, these efforts have fueled tensions, with many Sahrawis feeling marginalized and voiceless in their own land.

Algeria and Regional Dynamics

The Western Sahara conflict is not just a bilateral issue; it has become a cornerstone of regional rivalry, particularly between Morocco and Algeria. Algeria’s support for the Polisario Front and its hosting of the Tindouf camps have heightened tensions with Morocco, leading to a strained relationship characterized by periodic border closures and military buildups. Algeria views Western Sahara’s independence as a matter of principle, arguing that self-determination is essential to post-colonial sovereignty.

For Algeria, the conflict also serves as a counterbalance to Morocco’s influence in North Africa. The two countries have clashed diplomatically over the years, with Algeria opposing Morocco’s control over Western Sahara at international forums, while Morocco has called for Algeria to end its support of the Polisario. The rivalry has implications for the Maghreb’s stability, as both nations vie for influence in Africa and the broader Arab world.

A Frozen Conflict and Limited Prospects for Resolution

Decades after the ceasefire, Western Sahara remains a frozen conflict, a territory caught between Morocco’s claims of sovereignty and the Sahrawi desire for self-determination. Despite numerous rounds of UN-sponsored talks, no breakthrough has emerged. The referendum promised in 1991 remains stalled, while Morocco’s autonomy plan has gained diplomatic backing but lacks widespread acceptance as a solution.

The international community remains divided, with some countries supporting Morocco’s sovereignty, others backing Sahrawi self-determination, and many choosing not to take a firm stance. The European Union, for example, continues to engage diplomatically with both Morocco and the Polisario but has refrained from fully endorsing either position. The UN, meanwhile, remains committed to a negotiated solution, though its peacekeeping mission faces the challenge of enforcing a ceasefire without clear progress toward a permanent resolution.

Conclusion: The Unfulfilled Promise of Self-Determination

Western Sahara stands as one of the last colonial conflicts in Africa, a reminder of the complexities of decolonization and the often-overlooked struggles for sovereignty. For the Sahrawi people, the dream of an independent homeland remains strong but elusive, trapped in a political stalemate that has kept thousands in refugee camps for generations. Morocco, for its part, has fortified its presence in Western Sahara, building infrastructure, asserting control, and seeking to legitimize its claim through diplomacy.

As the conflict enters its fifth decade, the prospects for a peaceful resolution seem distant. Western Sahara’s fate remains intertwined with larger geopolitical rivalries, from North African regional tensions to global diplomatic maneuvers. In the end, the

hope for a peaceful and just resolution in Western Sahara rests on the commitment of all parties involved to prioritize the rights and aspirations of the Sahrawi people. Yet, as long as political interests, economic incentives, and regional rivalries take precedence, the path to lasting peace and self-determination remains fraught with obstacles.

Looking Ahead: The Quest for Peace and the Role of the International Community

The international community’s role in Western Sahara’s future is crucial, yet deeply complicated. The UN’s continued presence through MINURSO reflects a commitment to peace but also highlights the limitations of diplomacy without enforcement mechanisms or unified support from global powers. While the United States’ 2020 recognition of Moroccan sovereignty has emboldened Morocco’s position, other nations and regional blocs, including the African Union, remain vocal supporters of the Sahrawi people’s right to self-determination.

Ultimately, sustained international pressure will be necessary to reinvigorate negotiations and push for meaningful progress. Many advocates argue that the UN could play a stronger role by implementing a transparent and unbiased referendum process or mediating new frameworks for compromise that are acceptable to both Morocco and the Polisario Front.

The Humanitarian Crisis and the Generational Impact

Beyond the political complexities lies the human toll. For generations, Sahrawi families have been divided, with some residing in refugee camps in Algeria and others living under Moroccan control in Western Sahara. These camps have become home to young people who have known no other life, living in limbo and yearning for an identity they have yet to fully experience. The frustration and disillusionment among these youth are palpable, as hopes for independence appear increasingly remote.

In Moroccan-controlled Western Sahara, economic investment and development have brought some benefits, but also deepened resentment among those who feel their cultural and political rights are being eroded. The presence of Moroccan settlers and the integration of the region’s resources into Morocco’s economy have further marginalized the Sahrawi population, leading to clashes and crackdowns on pro-independence activism.

Conclusion: A Conflict Frozen in Time, But Not Forgotten

Western Sahara’s struggle represents one of the world’s longest unresolved conflicts—a case of colonial legacy, geopolitical rivalry, and the challenge of upholding international principles of self-determination. For the Sahrawi people, the promise of independence remains a powerful symbol of identity and justice, one that has inspired resilience despite decades of adversity. For Morocco, Western Sahara is seen as inseparable from the nation’s territorial integrity, a matter of national pride and security.

As the world watches, the people of Western Sahara continue to endure, caught between power struggles far larger than themselves. Until a solution is reached, Western Sahara will remain a poignant example of the unfulfilled promises of decolonization, a place where the call for justice and the right to determine one’s future echoes across a landscape of sand and silence. In the end, Western Sahara’s story is more than just a political conflict; it is a testament to the enduring human spirit, a reminder that peace and dignity are aspirations worth fighting for, no matter how distant they may seem.

Leave a comment