Somalia: Conflict, Resilience, and the Pursuit of Stability

Introduction

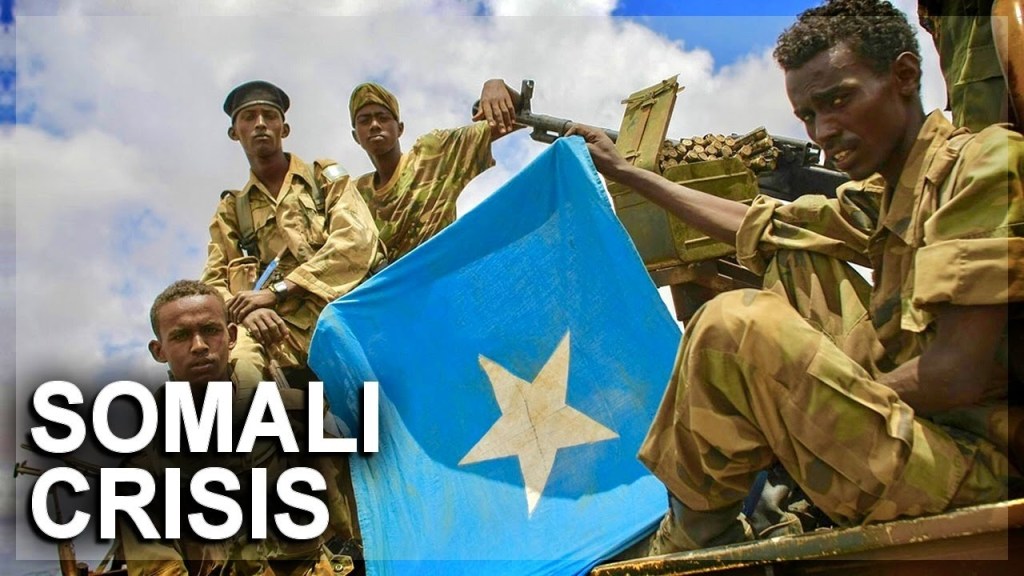

Somalia, a country on the Horn of Africa, is known both for its rich cultural heritage and for its decades of political instability, conflict, and humanitarian crises. Since the fall of its central government in 1991, Somalia has been portrayed as a land of warlords, pirates, and famine—a country emblematic of “failed state” narratives. However, this perspective only captures part of the story. Somalia’s journey includes remarkable resilience, efforts to rebuild, and an enduring hope for stability. As the nation struggles with internal divisions, terrorism, and foreign intervention, it is also finding paths toward unity and recovery. Today, Somalia stands at a crossroads, with its future shaped by both formidable challenges and emerging opportunities.

Historical Context: Colonial Carve-Up and Struggles for Unity

Somalia’s modern history was shaped by colonialism. In the late 19th century, Britain, Italy, and France divided the Somali territories into British Somaliland, Italian Somaliland, and French Somaliland (now Djibouti), while a portion was absorbed by Ethiopia. Despite colonial borders, the Somali people shared a unified cultural identity, defined by language, Islam, and clan affiliations.

Somalia gained independence in 1960, with British Somaliland and Italian Somaliland merging to form the Somali Republic. However, the new state inherited a complex web of clan loyalties and regional divisions, along with aspirations for uniting all Somali territories—a concept known as “Greater Somalia.” These nationalist dreams fueled tensions with neighboring Ethiopia and Kenya, leading to the Ogaden War (1977–1978), in which Somalia sought control over the Somali-inhabited Ogaden region in Ethiopia. After a costly defeat, Somalia’s dream of Greater Somalia was crushed, straining the country’s economy and fostering internal discontent.

The Siad Barre Regime: Authoritarian Rule and Collapse (1969–1991)

Somalia’s early post-independence years were marked by democratic governance, but in 1969, Major General Siad Barre seized power in a coup, installing a military dictatorship. Barre promoted a vision of scientific socialism, nationalizing industries and attempting to modernize the economy. However, his regime relied heavily on clan-based favoritism, using repressive tactics to maintain power and suppress dissent.

In the 1980s, Somalia faced economic collapse and growing disillusionment with Barre’s authoritarianism. As opposition mounted, Barre’s government became increasingly violent, particularly in its brutal repression of the Isaaq clan in the north, which was accused of supporting anti-government rebels. By the late 1980s, Barre’s regime was crumbling under the weight of internal insurgencies and economic hardship. In 1991, he was overthrown, leaving Somalia without a central government and plunging it into a chaotic civil war.

Civil War and State Collapse: A Nation in Turmoil (1991–2000s)

After Barre’s fall, Somalia fragmented into warring factions led by clan-based warlords, each vying for control over territory and resources. The collapse of the state led to widespread violence, humanitarian crises, and mass displacement. Efforts to establish a central government faltered repeatedly as competing warlords, including Mohamed Farrah Aidid, refused to cede power. The lack of a stable government created a vacuum that plunged Somalia into lawlessness, with violent conflict ravaging cities and destabilizing rural areas.

In 1992, as famine gripped the country, the United Nations intervened with a humanitarian mission (UNOSOM I) to provide aid and restore order. However, the mission faced challenges from local militias, leading to the U.S.-led Operation Restore Hope. Although initially successful in distributing aid, the mission suffered setbacks, most notably during the 1993 Battle of Mogadishu, where 18 U.S. soldiers were killed in a confrontation with Aidid’s forces. The incident led to the withdrawal of U.S. troops and a scaled-back UN presence, effectively leaving Somalia’s fate in the hands of local factions.

Throughout the 1990s and early 2000s, Somalia remained a fragmented society with no functioning central government. The self-declared state of Somaliland in the north and the autonomous region of Puntland in the northeast established relative stability, while southern Somalia experienced continued chaos, with warlords ruling over fiefdoms and violence endemic across much of the territory.

Rise of Islamist Movements: The ICU and Al-Shabaab

By the early 2000s, Islamist groups began to fill the void left by failed governments and clan-based warlords. The Islamic Courts Union (ICU), a coalition of Sharia-based courts, emerged as a force promising security, justice, and an end to lawlessness. By 2006, the ICU had seized control of Mogadishu and significant parts of southern Somalia, gaining popular support for its ability to impose order.

However, the ICU’s rise alarmed both neighboring Ethiopia and the United States, which feared that Somalia could become a haven for Islamist extremism. In late 2006, Ethiopia, with U.S. support, launched a military intervention, driving the ICU out of Mogadishu and restoring the weak, internationally backed Transitional Federal Government (TFG). Yet, the intervention inadvertently fueled a radical insurgency, as the ICU’s hardline factions reorganized as Al-Shabaab, a militant Islamist group with ties to Al-Qaeda.

Al-Shabaab capitalized on local grievances, launching a violent insurgency against the TFG and Ethiopian forces. The group expanded its control over large parts of southern and central Somalia, imposing strict Sharia law and committing widespread human rights abuses. Al-Shabaab’s influence and violent campaigns not only destabilized Somalia but also posed a growing regional threat, leading to deadly attacks in Kenya, Uganda, and beyond.

Efforts at Rebuilding: The Federal Government and AMISOM

In 2012, Somalia took steps toward rebuilding a central government with the establishment of the Federal Government of Somalia (FGS), marking the first internationally recognized government since the collapse of Barre’s regime. The African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM), launched in 2007, provided crucial support, bolstering Somali forces in their fight against Al-Shabaab and reclaiming key cities, including Mogadishu.

Despite progress, the FGS has struggled to assert control beyond Mogadishu. Clan rivalries, corruption, and weak institutions continue to hinder effective governance. Somalia’s federal system aims to give autonomy to regional states while uniting the country under a central government, but this approach has often fueled power struggles between the federal government and regional authorities, such as Puntland and Jubaland, complicating Somalia’s quest for stability.

AMISOM’s presence, along with continued international support, has helped weaken Al-Shabaab, but the group remains resilient, exploiting local grievances and conducting frequent attacks. The Somali government’s limited capacity and reliance on foreign aid have raised concerns about the sustainability of progress in the absence of robust domestic institutions.

The Somali Diaspora: A Source of Resilience and Influence

Somalia’s decades of conflict have led to a large diaspora, with millions of Somalis living in Europe, North America, and neighboring African countries. The diaspora has become a vital economic lifeline for Somalia, sending billions of dollars in remittances annually. This influx of funds supports families, businesses, and local economies, filling the gap left by a weak formal economy.

Beyond economic contributions, the Somali diaspora has played an influential role in politics, development, and peacebuilding. Many Somali professionals have returned to participate in reconstruction efforts, while others lobby for international support and awareness of Somalia’s challenges. However, the diaspora’s involvement is not without complexity, as clan dynamics and political allegiances sometimes play out within diaspora communities, influencing both Somali politics and international perceptions.

Piracy and International Attention

In the late 2000s, Somali piracy emerged as a global security threat, as organized criminal networks hijacked commercial vessels off the Somali coast, demanding substantial ransoms. The root causes of piracy were complex, stemming from a combination of poverty, the lack of a functioning government, and grievances over illegal fishing by foreign vessels in Somali waters.

International naval coalitions, including the European Union’s Operation Atalanta and NATO forces, launched anti-piracy missions, reducing piracy incidents significantly by the mid-2010s. However, piracy highlighted the importance of addressing the economic and political void in Somalia’s coastal communities, underscoring the need for comprehensive solutions beyond military intervention.

Humanitarian Crisis: Famine, Drought, and Displacement

Somalia’s protracted conflict and political instability have created one of the world’s most severe humanitarian crises. Droughts, food shortages, and weak infrastructure have made Somalia particularly vulnerable to famine, with the worst crisis occurring in 2011, when over 250,000 people died due to famine exacerbated by conflict and Al-Shabaab’s restrictions on aid access.

Climate change has intensified these challenges, with recurrent droughts further destabilizing agricultural and pastoral livelihoods, leading to increased displacement. Today, millions of Somalis remain internally displaced or live as refugees, struggling to access basic services and food security. Humanitarian organizations, often restricted by security concerns, have worked to provide relief, but sustainable solutions are limited by ongoing conflict and political instability.

Conclusion: Somalia’s Path Forward

Somalia’s journey over the past three decades reflects both the costs of state collapse and the resilience of its people. Despite continued challenges, there are signs of progress. Efforts to rebuild government institutions, combat terrorism, and foster economic stability have offered glimpses of hope. Somalia’s youth, its largest demographic, embody a potential for change, as a generation born into conflict seeks peace, stability, and opportunity.

Somalia’s future hinges on its ability to strengthen governance, resolve clan rivalries, and develop a sustainable economy that addresses the

…needs of its people. Continued international support, particularly in security, development, and humanitarian aid, will be crucial. However, long-term stability depends on building local capacity and institutions that can operate independently, bridging divisions between the central government and regional authorities, and addressing the root causes of extremism and conflict.

Somalia’s resilience has been remarkable, reflected in the strength of its diaspora, the tenacity of its people, and the commitment of those working toward peace. As Somalia navigates its way forward, its story remains a powerful example of both the challenges and the possibilities that lie in the path from conflict to recovery. With a foundation rooted in both tradition and aspiration, Somalia has the potential to transform itself from a symbol of instability into a model of resilience and self-determination on the African continent.

Leave a comment