Myanmar: A Nation Divided by Struggle, Hope, and the Fight for Democracy

Introduction

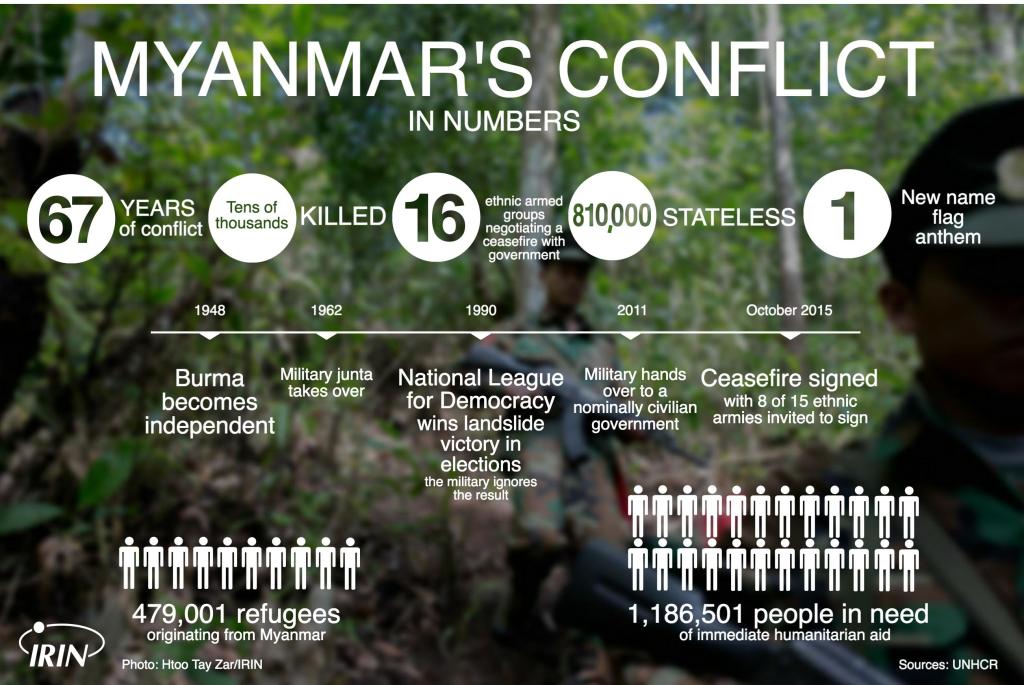

Myanmar, known to the world as Burma until 1989, is a land rich in cultural heritage, ethnic diversity, and untapped resources. Yet, this Southeast Asian nation has been wracked by decades of military rule, ethnic conflict, and, most recently, a brutal crackdown on democracy. For over half a century, Myanmar’s journey has been one of resilience against oppression, where cycles of hope for freedom have often given way to brutal repression. Today, the people of Myanmar stand at a crossroads, facing a repressive military junta with courage and determination. Myanmar’s struggle is not merely a national issue; it is a fight that resonates globally as a testament to the enduring human desire for freedom and justice.

Colonial Legacy and Independence (1824–1948)

The roots of Myanmar’s modern-day turmoil stretch back to its colonial past. For over a century, Myanmar was part of the British Empire, after a series of Anglo-Burmese Wars (1824–1885) that brought the entire region under British rule. This period was marked by cultural and political upheaval, as the British colonial administration dismantled Myanmar’s monarchy, altered its landownership structure, and imposed foreign systems of governance.

During World War II, Myanmar became a strategic battleground. Nationalist forces, initially aligning with the Japanese, fought the British with the hope of independence, only to later turn against the Japanese. After the war, the British finally granted independence in 1948, and Myanmar emerged as a newly sovereign state. However, the transition was tumultuous. Ethnic groups who had been promised autonomy during colonial rule were now embroiled in tensions with the central government, sowing the seeds of conflicts that persist to this day.

The First Coup and Decades of Military Rule (1962–1988)

In 1962, a coup led by General Ne Win installed a military dictatorship, marking the beginning of nearly five decades of military control. Ne Win imposed the “Burmese Way to Socialism,” a doctrine that nationalized industries and isolated the country from the global economy, leading to economic stagnation and poverty. Myanmar’s military rulers exercised tight control over political life, cracking down on dissent and stifling freedom of speech, leaving citizens under a repressive regime.

Ethnic tensions intensified under Ne Win’s rule. Myanmar is home to more than 135 ethnic groups, each with distinct cultures and languages, including the Kachin, Karen, Shan, and Rohingya. The central government’s policies of “Burmanization,” aimed at promoting the majority Bamar culture, marginalized these groups, sparking insurgencies and fueling resentment that persists today. The military used brutal tactics to suppress ethnic insurgents, committing widespread human rights abuses, including forced displacement, torture, and mass killings.

In 1988, mounting public discontent over economic hardship and authoritarianism led to nationwide protests, known as the 8888 Uprising. Hundreds of thousands took to the streets, demanding democratic reforms. The military’s response was brutal: soldiers opened fire on protesters, killing thousands. However, the uprising brought Aung San Suu Kyi, daughter of independence hero General Aung San, to the forefront, as she became a symbol of hope and resilience.

The Rise of Aung San Suu Kyi and the “Democracy Spring” (1990–2010)

Following the crackdown, the military junta, now rebranded as the State Law and Order Restoration Council (SLORC), called elections in 1990, expecting to legitimize its rule. However, in a landslide victory, Aung San Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy (NLD) won the majority of seats. Instead of ceding power, the military annulled the results and placed Suu Kyi under house arrest, where she would spend 15 of the next 21 years.

Despite repression, Suu Kyi’s reputation grew internationally. Her peaceful advocacy for democracy earned her the Nobel Peace Prize in 1991, and she became a symbol for democratic movements worldwide. Meanwhile, Myanmar’s economy suffered under sanctions imposed by Western countries in response to human rights abuses. The military junta maintained a tight grip, using surveillance, forced labor, and censorship to stifle any dissent.

In 2008, the military drafted a new constitution that cemented its power but allowed for a partial opening of the political system. The constitution reserved 25% of parliamentary seats for the military, giving it veto power over constitutional changes, and retained control over key ministries. Nonetheless, the partial reform paved the way for limited civilian rule, and in 2010, Myanmar held its first elections in decades. Although these elections were boycotted by the NLD, they marked the beginning of a cautious transition.

The “Golden Years” and a Fragile Democracy (2015–2020)

In 2015, Myanmar held its first relatively free election, and the NLD achieved a historic victory. Aung San Suu Kyi, barred from the presidency by the military-drafted constitution, became the de facto leader, assuming the title of “State Counsellor.” Myanmar seemed poised for a new era, with diplomatic ties with the West improving, economic sanctions lifting, and foreign investments trickling in.

However, the challenges of governance soon became evident. The military retained considerable power and remained a formidable force in politics. Moreover, Suu Kyi’s reputation took a severe hit internationally over the Rohingya crisis. In 2017, the military launched a violent crackdown on the Rohingya Muslim minority in Rakhine State, forcing over 700,000 to flee to Bangladesh. Reports of mass killings, sexual violence, and burning of villages led the UN to describe it as a “textbook example of ethnic cleansing.” Suu Kyi’s refusal to condemn the military and her defense of its actions at the International Court of Justice shocked many, tarnishing her legacy as a champion of human rights.

Domestically, ethnic conflicts continued, with fighting intensifying in Kachin and Shan states. The peace process, which Suu Kyi had championed, stalled as ethnic groups grew increasingly skeptical of both the NLD and the military. While Myanmar’s democracy brought hope, it was fragile, marred by internal divisions, ethnic tensions, and an empowered military.

The 2021 Coup: Democracy Interrupted

In February 2021, just as the NLD was preparing to start its second term after another electoral victory, the military seized power in a coup, arresting Suu Kyi and other leaders. The junta, led by Commander-in-Chief Min Aung Hlaing, justified the takeover with unsubstantiated claims of election fraud. The coup sparked massive protests, strikes, and a civil disobedience movement as Myanmar’s population, having tasted democracy, refused to return to military rule.

The military’s response to the protests was brutal, echoing its tactics from past uprisings. Security forces used live ammunition, tear gas, and mass arrests to quell demonstrations. Over 1,000 civilians have been killed, and thousands more imprisoned or displaced. The conflict has reignited ethnic insurgencies, with some groups aligning themselves with the anti-junta resistance, leading to a multi-front civil conflict. The economy has suffered deeply, with the collapse of foreign investment and worsening poverty levels.

The junta’s violent crackdown has prompted renewed sanctions and condemnation from the international community, but diplomatic efforts to broker peace have largely stalled. Regional actors, including ASEAN, have struggled to find a unified approach, with Myanmar’s neighbors balancing their economic interests with a desire for regional stability. Meanwhile, the people of Myanmar face a humanitarian crisis, with widespread displacement, food insecurity, and human rights abuses escalating.

The Role of Ethnic Groups and the Rise of the National Unity Government

Myanmar’s ethnic groups, many of whom have fought for autonomy since independence, now play a crucial role in the resistance. Groups like the Karen National Union (KNU) and the Kachin Independence Army (KIA) have provided shelter and support to anti-junta activists, while other ethnic armed organizations have ramped up their fight against the military. This alignment has given rise to a more unified opposition, albeit one with complex and sometimes conflicting goals.

In exile, Myanmar’s elected lawmakers and pro-democracy activists formed the National Unity Government (NUG), which has garnered significant support from the diaspora and segments of the international community. The NUG has vowed to dismantle the 2008 constitution and create a federal democratic union, addressing long-standing demands for ethnic representation. However, without control over the country or military resources, the NUG faces immense challenges in its fight for legitimacy and recognition.

Myanmar’s Place in Regional and Global Geopolitics

The crisis in Myanmar holds significant regional implications, particularly as China and India, its powerful neighbors, weigh their interests. China, which shares a border with Myanmar, has maintained a cautious stance, balancing its support for the military with ties to ethnic groups near its border and with economic interests, including infrastructure projects under the Belt and Road Initiative. India, too, has concerns about instability spilling over its borders, along with an interest in countering Chinese influence in Myanmar.

ASEAN, traditionally committed to non-interference, has attempted to mediate, though divisions within the bloc have limited its effectiveness. The UN and Western countries, including the U.S. and EU, have imposed sanctions on the military junta, but efforts to enact a broader international response are hindered by geopolitical tensions, particularly between China and the West.

Conclusion: A Long Road to Freedom and Reconciliation

Myanmar’s fight for democracy is far from over. For decades, its people have shown incredible resilience, rallying against oppression and enduring the hardships of military rule. Yet the 2021 coup has plunged the country back into turmoil

, erasing hard-won democratic gains and pushing Myanmar toward an uncertain and turbulent future. For the people of Myanmar, the struggle for freedom is not just a political battle but a profound test of endurance, unity, and hope against a regime willing to use brutal force to maintain control.

The military junta’s grip on power has placed Myanmar in a volatile state where ethnic, political, and social divisions run deep. Despite the harsh repression, however, the spirit of resistance remains unbroken. Young people, civil servants, monks, ethnic leaders, and ordinary citizens continue to demonstrate and participate in acts of defiance, forming a broad coalition that reflects a rare unity across Myanmar’s diverse society.

A Struggle for Identity and a Vision of a Federal Myanmar

One of the most significant changes since the coup has been the call for a truly federal Myanmar—a political system that would recognize and respect the country’s ethnic diversity and the rights of its different communities. This vision addresses a long-standing grievance that ethnic groups have held since independence: the desire for self-governance, respect for cultural identity, and a fair share of political power.

The National Unity Government (NUG) has embraced this federalist vision, recognizing the need to address ethnic minorities’ demands as part of the democratic movement. For many ethnic communities, particularly those who have suffered under Burman-dominated central rule, this acknowledgment is a crucial step. The concept of a federal Myanmar not only offers a path to national unity but also serves as a potential framework for ending decades of ethnic insurgencies and fostering peace.

The Path Forward: Challenges and Glimmers of Hope

Myanmar’s path forward is littered with obstacles. The military’s deep-rooted influence, entrenched economic networks, and foreign alliances make it a formidable adversary. Any diplomatic solution requires navigating complex geopolitics, where the interests of China, ASEAN, India, and Western powers often diverge. The international community’s efforts to apply pressure through sanctions and diplomacy have had limited success, as the junta remains unyielding and insulated by support from certain regional allies.

However, the people of Myanmar have demonstrated that they are far from powerless. Grassroots resistance, whether in the form of strikes, civil disobedience, or guerrilla tactics, continues to disrupt the military’s authority. The emergence of the National Unity Government has given the people a rallying point, an alternative vision of governance that promises a future based on democracy and inclusion.

Conclusion: Myanmar’s Unfinished Revolution

Myanmar’s struggle is more than a fight between a junta and a pro-democracy movement; it is a deep-rooted quest for identity, unity, and justice. The sacrifices made by generations of activists, from Aung San Suu Kyi to today’s young protestors, underscore the strength of the people’s commitment to a better future. Yet, the cost of this fight is devastating: thousands of lives lost, livelihoods destroyed, and a nation scarred by division and violence.

The dream of a democratic Myanmar—a nation where diverse ethnicities and religions coexist with mutual respect—remains distant but not impossible. The journey is far from over, but as long as the people of Myanmar continue to fight, resist, and hope, they carry forward the legacy of resilience that has defined them for generations. The world watches with bated breath, knowing that Myanmar’s future is a powerful testament to both the brutality of oppression and the unbreakable spirit of those who dare to resist it.

Leave a comment