Cyprus: A Divided Island and the Quest for Reunification

Introduction

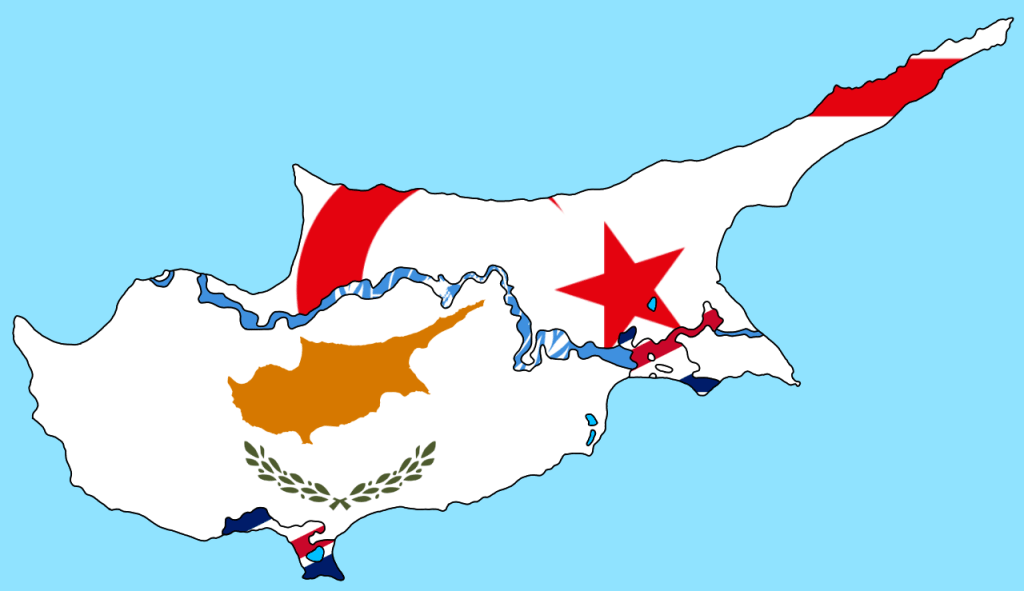

Cyprus, a Mediterranean island with a history of ancient civilizations, has become a modern-day symbol of division and geopolitical tension. For decades, Cyprus has been split between its Greek Cypriot south and Turkish Cypriot north, separated by a UN-patrolled buffer zone. The island’s division stems from historical, ethnic, and political tensions, intensified by the interests of regional powers and a legacy of colonial rule. While there have been multiple attempts at reunification, Cyprus remains one of the world’s longest-standing frozen conflicts. Today, as new energy resources emerge in the Eastern Mediterranean and EU-Turkey relations shift, Cyprus’s future hangs in the balance, symbolizing both the possibility and challenges of reconciliation in a divided world.

Historical Context: Colonial Rule and Ethnic Divides

Cyprus’s modern political divisions can be traced back to British colonial rule, which began in 1878. The island was strategically valuable to the British Empire, serving as a key base in the Mediterranean and offering a gateway to the Middle East. Under British administration, ethnic divisions between Greek Cypriots (predominantly Greek Orthodox Christians) and Turkish Cypriots (predominantly Muslim) became more pronounced.

In the 1950s, the Greek Cypriot community launched a movement to achieve “Enosis,” or union with Greece. The campaign, led by the National Organization of Cypriot Fighters (EOKA), aimed to end British rule and unify Cyprus with Greece. The Turkish Cypriot minority, however, feared being marginalized under Greek rule and sought “Taksim” (partition), supporting a division that would create a Turkish-administered region in Cyprus. As violence escalated, the British ultimately withdrew, leaving the island’s fate to a fragile power-sharing agreement under an independent Republic of Cyprus established in 1960.

Independence and the Makarios Era (1960–1974)

The Republic of Cyprus gained independence from Britain in 1960, with a power-sharing arrangement enshrined in a constitution. Archbishop Makarios III, a prominent Greek Cypriot leader, became the island’s first president, while Turkish Cypriot leader Dr. Fazıl Küçük became vice president. The independence agreement included guarantees from Britain, Greece, and Turkey to protect the island’s sovereignty and maintain peace between its ethnic communities.

However, Cyprus’s independence did little to ease tensions between Greek and Turkish Cypriots. Political disagreements and communal violence erupted, as each side struggled to secure its interests within the new republic. In 1963, the power-sharing government collapsed, and inter-ethnic violence ensued, prompting the United Nations to establish a peacekeeping mission (UNFICYP) that still operates today. The resulting separation of communities set the stage for the division that would follow.

The 1974 Invasion: Division of the Island

The turning point came in 1974, when a coup orchestrated by Greek Cypriot nationalists and backed by Greece’s ruling military junta aimed to achieve Enosis. In response, Turkey, citing its role as a guarantor under the 1960 treaty, launched a military intervention on the island to protect Turkish Cypriots and prevent Cyprus from becoming a Greek-dominated state. The invasion resulted in the division of Cyprus, with Turkey controlling the northern third of the island and displacing thousands of Greek Cypriots from their homes. This division led to significant human suffering, with tens of thousands of Cypriots displaced from both communities.

Since 1974, Cyprus has remained divided, with the internationally recognized Republic of Cyprus governing the south and the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC) in the north. The TRNC declared independence in 1983 but is recognized only by Turkey. A UN-patrolled buffer zone, known as the “Green Line,” stretches across the island, creating a de facto border and symbolizing the unresolved conflict.

UN Mediation and Reunification Efforts: The Annan Plan and Beyond

Since the 1974 division, multiple attempts have been made to resolve the Cyprus issue, with the United Nations leading mediation efforts. The most comprehensive plan came in 2004 with the Annan Plan, named after then-UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan. The plan proposed a federal solution, creating a bicommunal, bizonal federation with political equality for Greek and Turkish Cypriots. The Annan Plan was put to a referendum, with Turkish Cypriots voting in favor, while Greek Cypriots overwhelmingly rejected it, fearing it would legitimize the Turkish occupation and weaken their control over the island.

The rejection of the Annan Plan revealed deep-seated mistrust and different expectations between the two communities. Greek Cypriots sought greater security and the withdrawal of Turkish troops, while Turkish Cypriots wanted assurances of political equality. The failed referendum stalled reunification efforts, and Cyprus joined the European Union later that year, with EU laws applying only in the south.

EU Membership and Its Impact on the Cyprus Issue

Cyprus’s accession to the European Union in 2004 reshaped the conflict, adding a new layer of complexity to the reunification process. Although only the Republic of Cyprus (the Greek Cypriot south) enjoys full EU membership benefits, Turkish Cypriots are EU citizens by virtue of their Cypriot nationality. The EU’s involvement in the Cyprus issue has added pressure on Turkey, which aspires to join the EU but faces obstacles due to its refusal to recognize the Republic of Cyprus.

EU membership has provided the Greek Cypriot government with additional leverage in negotiations, as Turkey’s EU accession process is indirectly tied to progress on Cyprus. However, the deadlock continues, and Turkey’s EU ambitions have waned, reducing the potential for the EU to influence Turkey’s position on Cyprus.

Regional Tensions: Energy Resources in the Eastern Mediterranean

The discovery of significant offshore gas reserves in the Eastern Mediterranean in the 2010s introduced a new dimension to the Cyprus conflict. Both the Republic of Cyprus and Turkey have laid claim to the gas fields, with the Turkish government asserting rights on behalf of Turkish Cypriots in the north. The Republic of Cyprus, meanwhile, has signed exploration agreements with companies from Italy, France, and the United States, further complicating the issue.

Turkey has responded by deploying exploration vessels and military escorts in contested waters, creating a volatile situation that has drawn in other regional actors, including Greece and Egypt. The energy dispute has intensified the rivalry between Turkey and Greece and raised concerns within the EU and NATO about security and stability in the Eastern Mediterranean. The gas reserves, initially seen as an economic boon for Cyprus, have instead highlighted the island’s division and deepened regional tensions.

Current Status: A Frozen Conflict and Glimmers of Hope

Despite these challenges, recent years have seen some glimmers of hope for a diplomatic breakthrough. Leaders from both communities, including Turkish Cypriot leader Mustafa Akinci and his Greek Cypriot counterpart Nicos Anastasiades, have engaged in dialogue, with both expressing support for reunification under a federal model. However, negotiations remain fraught, with key issues—including property rights, the presence of Turkish troops, and power-sharing arrangements—remaining unresolved.

One sticking point is the Turkish Cypriot demand for political equality, which includes rotating the presidency between Greek and Turkish Cypriots. The Greek Cypriot side, however, fears that this arrangement would reduce their influence and increase Turkish control over the island’s political landscape. These disagreements underscore the mistrust that has long plagued reunification efforts.

The Role of External Powers: Turkey, Greece, the UK, and the UN

Cyprus’s strategic location has drawn the involvement of several external powers. Turkey maintains a military presence in the north, while Greece and the United Kingdom, as former colonial powers, retain vested interests in the island’s future. The UK still operates two sovereign military bases in Cyprus, which are seen as strategically valuable for operations in the Middle East.

The United Nations continues to oversee the Green Line through the UN Peacekeeping Force in Cyprus (UNFICYP), one of the longest-standing UN missions. Additionally, the EU, as a guarantor of Cypriot membership, has advocated for a peaceful resolution to the conflict. Each of these actors has its own agenda, and their involvement complicates the negotiations between the Greek and Turkish Cypriot communities.

Conclusion: Cyprus at a Crossroads

The Cyprus conflict is a stark reminder of how historical grievances, nationalism, and external interests can create a seemingly intractable situation. For decades, the division of Cyprus has resisted numerous efforts at reconciliation, even as global and regional politics evolve around it. While both communities express a desire for peace, the deep-seated mistrust and competing narratives make compromise elusive. As the island navigates the future, the discovery of natural gas resources and shifting geopolitical alliances may either serve as catalysts for reunification or deepen the divide.

For now, Cyprus remains a divided island, a place where barbed-wire fences and checkpoints separate families and communities. Yet, the possibility of reunification endures, kept alive by a generation of Cypriots who remember a unified past and dream of a future free from division. Cyprus’s story is one of resilience, identity, and the search for lasting peace, a reminder that even the longest-standing conflicts can find paths toward reconciliation if there is the will to build a shared future.

Leave a comment